Floodline

How the Great Flood of 1937 brought two Kentuckians — and the family that followed — to higher ground.

Before the water came, before the city turned to river, before a man rowed through a drowned street to reach the woman he’d only just met — there was Aunt Mag.

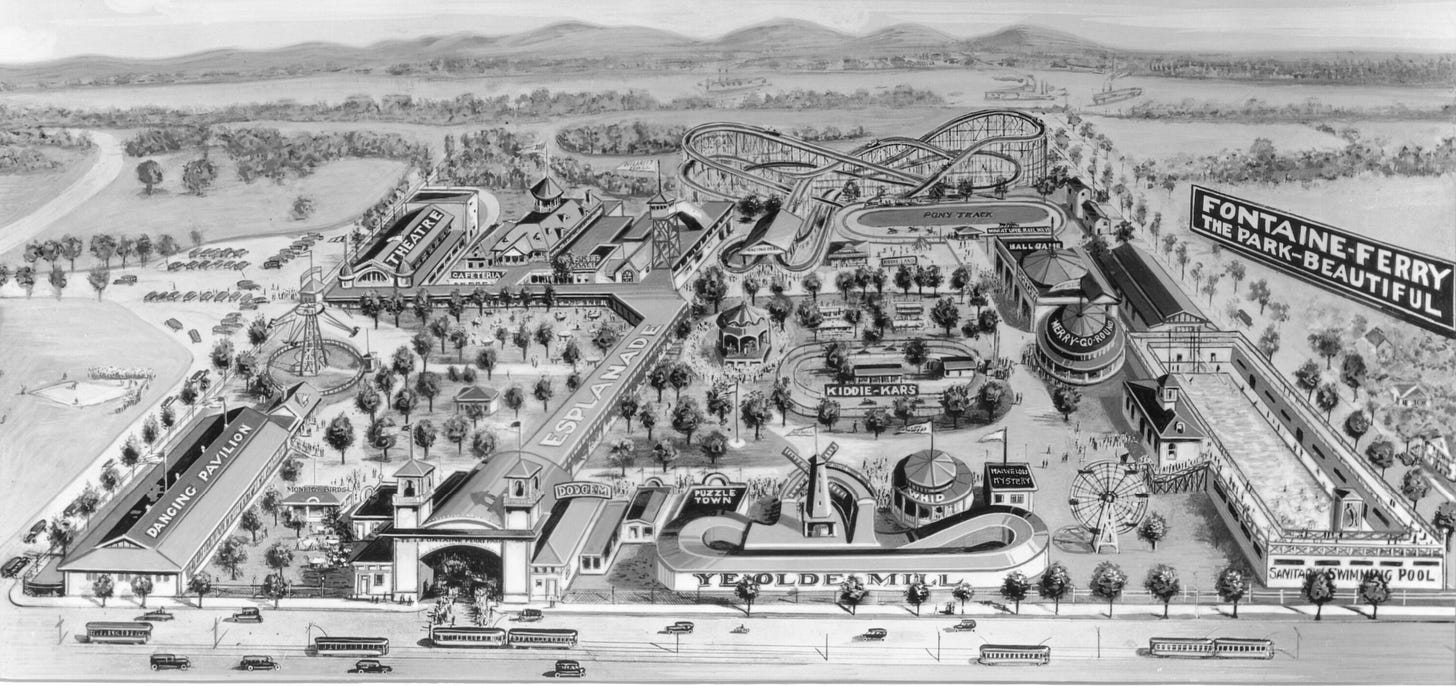

Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas had a romantic streak. She believed in timing, in fate, and in paying attention to the things other people missed. Working at Fontaine Ferry Amusement Park in the mid-1930s, she worked a ride and kept a watchful eye on her coworkers. One in particular stood out.

Mary Lee Zweydoff was graceful in a way that didn’t draw attention to herself. Friendly, poised, and always composed, she had inherited her mother’s German cheekbones and her father’s charm. She had an eye for beauty — not just in appearance, but in the way people moved, in color, in detail. It was a quiet gift that would stay with her, eventually leading her to become an artist at age fifty. She was the eldest daughter in a sprawling Catholic family of ten siblings. Born in the Portland neighborhood of Louisville on August 23, 1919, she’d grown up among the flatboats and floodplains, the clang of steamboat bells, and the hush of family stories told in kitchens over weak coffee and strong memories.

Her name — Mary Lee — was a bridge between two pasts. “Mary” for her maternal grandmother, Mary Louisa Rolfes Ringswald, who died before she was born. “Lee” for her paternal grandfather, Lee Zweydoff, whose name, passed down, was a whisper of older worlds: of Germany, of hardship, of a family that had long since made the Ohio River home.

Mag liked her immediately. But more than that — she saw something. She thought of her nephew: Wilbur Padgett, born on a Meade County farm on November 7, 1915. He was the second-oldest son of twelve, raised at the meeting point of Otter Creek and Dry Branch, where the land folded into itself and boys became men early. He had callused hands, a work-worn back, and eyes the color of Kentucky limestone under morning light.

Handsome, yes — but it wasn’t that. It was something steadier. Something you could trust.

“They both had pretty eyes,” Mag would say later. “And I thought they’d make a good match.”

So she made the match.

The blind date was set for New Year’s Day, 1937 — a holiday dance at the Casa Madrid Ballroom on Third and Guthrie. It was a night for pressed suits, polished shoes, and jazz slow enough to sway to. Mary Lee wore a simple dress and her favorite necklace. Wilbur stood tall in a well-fitted suit, sharp as ever. He dressed the way he carried himself — with quiet pride and intention.

They danced. Talked. She liked his quiet confidence. He liked the way her gaze held his without hesitation.

“He was a very good dancer,” Mary Lee would say decades later. “And he had really pretty eyes.”

They agreed to see each other again.

But life — and the Ohio River — had other plans.

The Ohio has always carried moods.

It’s been a lifeline, a boundary, a mirror — sometimes serene, sometimes brutal.

It has shaped cities, drawn borders, swallowed whole towns, and bound together the lives of those who built homes along its edge.

In winter, it broods under gray skies — cold, slow, and watchful.

In spring, it surges with memory, swollen with snowmelt and storms, as if reminding the valley who’s in charge.

Some years it whispers. Other years it roars.

For Louisville, the river has always been both blessing and warning —

wide, winding, not to be underestimated.

It brings commerce, connection, and beauty — but also danger.

It’s part of the landscape and the legend, always there, always waiting.

You don’t live beside the Ohio River without learning to respect its moods — or without wondering what it might take, and what it might give back.

And in January of 1937, the river took more than anyone was prepared to give.

The rains began almost immediately after their first meeting. A slow, persistent drizzle at first. Then a downpour. Day after day, the skies refused to clear. January 1937 brought twenty-three straight days of rain. The Ohio River, already swollen from a wet winter, surged. Creeks spilled their banks. The city’s stormwater systems failed. And then the river turned on the city and forgot mercy.

Flood stage came and went. By the third week of January, the water had risen more than 30 feet above normal. On January 27, the Ohio River crested at 52.15 feet — an unprecedented high. Seventy percent of Louisville lay underwater. Streetcars were stranded. Telephone lines snapped. Gas and electric services failed. Thousands fled, their belongings bundled on their backs.

Slevin Street, in the Portland neighborhood where Mary Lee’s family lived, was no exception.

The water came slowly, lapping at doorsteps like a visitor unsure whether to come in. Then it rose, relentless, swallowing sidewalks, porches, and parlors. The Zweydoff family tried to wait it out, but there was no end in sight. They needed to evacuate.

And that’s when Mary Lee sent word to Wilbur.

She didn’t ask him to come. She only told him what was happening. That was all he needed.

Wilbur found a canoe.

No one remembers where it came from — if it was borrowed, found, or fashioned. What’s remembered is what he did with it.

He paddled across streets that no longer had names, only currents. Past telephone poles that looked like river markers. Past drowned storefronts and submerged curbs. The city was eerily quiet, the way it gets after disaster takes the noise with it.

And then — there they were. The Zweydoffs, waiting on what remained of their front porch.

“When I saw his crystal blue eyes in the canoe that day,” Mary Lee said later, “I knew I wanted to be with him the rest of my life.”

He ferried them to safety — Mary Lee, her parents, her siblings. They stayed with relatives elsewhere in the city until the waters receded.

Sometimes, love doesn’t arrive with roses. Sometimes, it paddles.

The flood took everything. More than 175,000 residents were displaced. Damages rose to what today would be over a billion dollars. It would take decades to construct the 29-mile floodwall system the city now depends on.

But amid all that ruin, something took root — quietly, and without blueprint.

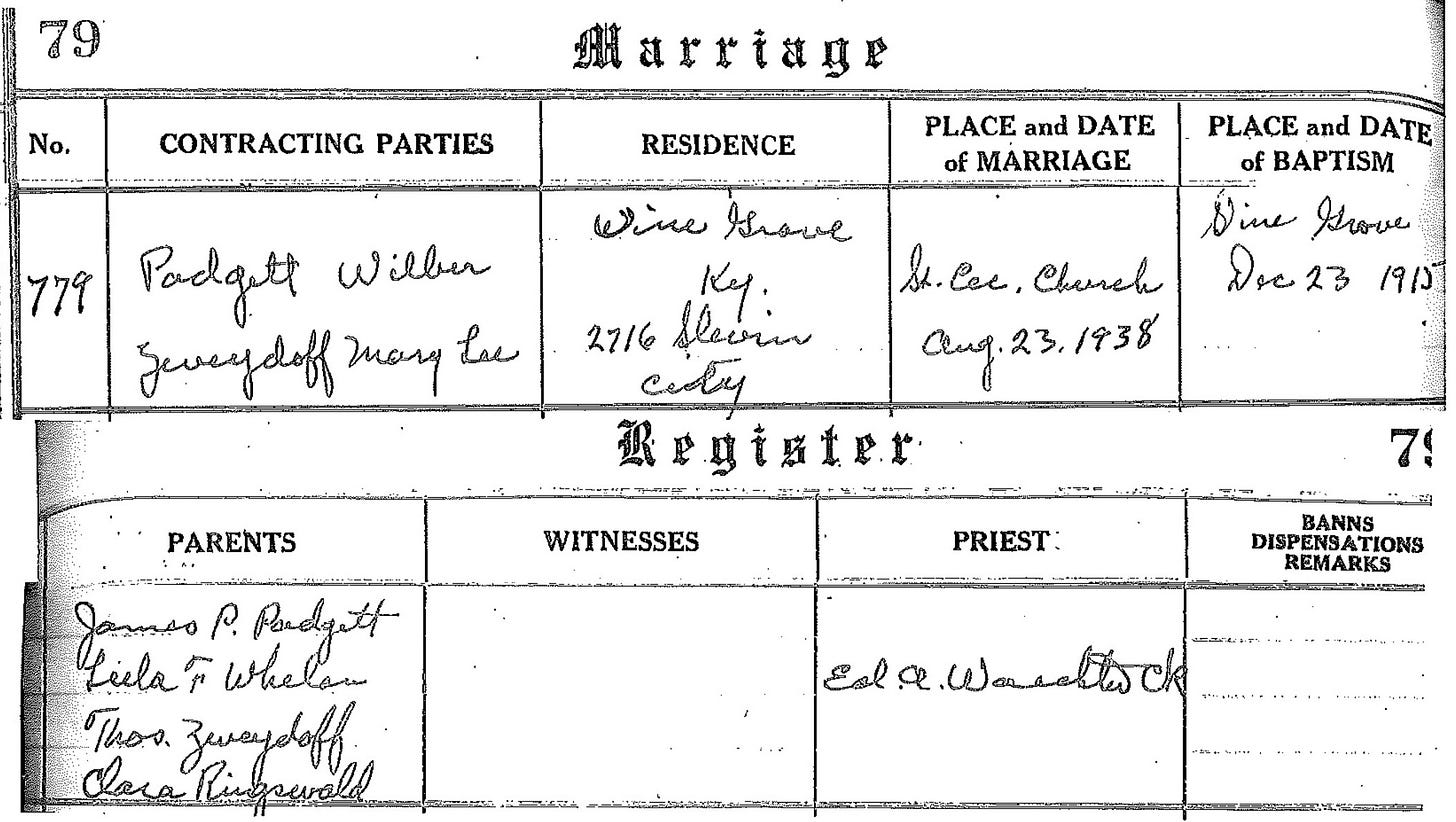

When spring came, Wilbur proposed. And on August 23, 1938 — Mary Lee’s 19th birthday — they were married at Saint Cecilia Catholic Church in Portland, where her parents had wed before her.

There was no spectacle. Just two families, four witnesses, and two hearts that had already known what it meant to endure.

They made a life together.

Eleven children. A house full of noise, love, and motion. Wilbur spent most of his career as a supervisor for Klarer, a Louisville-based meat processing company owned by the Broecker family. He worked with steadiness and integrity, earning respect not just for what he did, but how he did it. Mary Lee made their home a living canvass. The family grew. Years passed. A flood of a different kind — children, then grandchildren, then great-grandchildren — followed.

While he was a leader of people at his work, Wilbur was a storyteller at heart.

Around kitchen tables and front porches, he could spin a memory into something larger than life — funny, heartfelt, and always grounded in what mattered.

His stories held the generations together, giving shape to the past and a sense of belonging to those just arriving into it.

He wasn't just building a family.

He was building its memory — story by story, moment by moment — so that long after he was gone, the people he loved would still know where they came from, and who they belonged to.

In the 1970s and 80s, he also bred blue tick hounds — lean, vocal, and loyal — and sold them.

His prized dog was named Butch, a wiry creature with a knowing look and a howl that could split the night.

He loved those dogs — not just for their skill, but for their companionship.

And when he wasn’t with his hounds, he was often out on the water.

He kept his boat in the barn, ready for early mornings on Rough River or quiet afternoons at his camp in Axtell — casting lines, telling stories, and watching the light shift across the trees.

It was a rhythm that suited him: steady, unhurried, and never far from the land he loved.

Wilbur and Mary Lee were, at heart, a storyteller and an artist — shaping a life filled with memory, color, and love.

What they built wasn't just a home.

It was a world made by hand and heart — one that others would step into, carry forward, and never forget.

Mary Lee spent her final decades on a quiet farm in Meade County — land she and Wilbur bought in the 1970s, not far from where he’d grown up. It was a piece of history I had previously written about in I Remember It All Too Well: A Taylor Swift-Inspired Guide to Family History — land once lost to the expansion of Fort Knox.

They built their retirement home upon a hill, surrounded by mature trees, with a barn and a broad chicken coop, and gardens full of roses, irises, and lilies that bloomed across the seasons. The scent of old roses drifted through the summer air. A birdhouse stood high atop a pole, waiting each spring for the return of the purple martins. And just beside the porch, a cast-iron dinner bell hung from a post — ready to call family in for supper. That porch, wide and welcoming, became the heart of it all — where stories were passed down, laughter was shared, and the family she and Wilbur built gathered, again and again.

There, she built a life shaped by the things she loved: a sprawling garden, two ponds Wilbur had dug himself, chickens that kept the rhythm of the days, shelves of well-worn books, and the steady, patient creation of her landscape paintings.

She was a remarkable cook — humble in presentation, but gifted in flavor. Her pies were legendary; she’d often bake a dozen at a time, lining them up on the counter like a parade of comfort.

A German cuckoo clock hung on the kitchen wall, ticking softly above the table — a nod to the heritage she carried, and a quiet keeper of time in a house where time never felt rushed.

Family was never far from her doorstep. Her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren came often — gathering in the house, walking the fields, laughing by the ponds.

Weekends were spent in conversation. The television was rarely on, except for two quiet favorites that seemed to mirror her spirit: Victory Garden and The Joy of Painting with Bob Ross.

In that house, everything had a purpose. Everything had a pace. And everything — from her kitchen to her canvas — bore the mark of her care.

Wilbur died in the late summer of 1986 — sudden and without warning, as so many Padgett men seemed to go.

One moment he was there, steady as ever. The next, he was gone.

They had been married 48 years.

At his funeral, all eleven of his children contributed to his eulogy — a single voice built from many hearts.

They called him a husband, father, teacher, confidant, counselor, and friend.

”A man who never met a stranger.

One of those rare people who come along once in a lifetime — and when they’re gone, you realize a lifetime wasn’t enough.”

And just like that, Mary Lee found herself at the edge of a quieter season.

But she carried on — steady, strong, and surrounded by the family they had built.

Even after he was gone, Wilbur found his way into her artwork.

When Mary Lee finished a painting, she would sometimes ask him to sign it — not because she couldn’t, but because she still wanted him there.

It wasn’t common — an artist asking someone else to place the final mark on her work — but for her, it felt right.

Theirs had always been a shared life.

She created the landscapes. He added his hand.

And together, they signed their story — again and again, across canvas and time.

In every brushstroke, in every signature, he remained part of her canvas.

Their story never really ended.

It simply found new ways to take root and grow.

Mary Lee would outlive all of her siblings and reach the age of ninety-two — passing just four days after her birthday, and on what would have been her seventy-third wedding anniversary with Wilbur, as if her life had kept time with their love to the very end.

And Aunt Mag?

Her story came back to me decades later — at a dinner held exactly seventy-five years after the night she sent my grandparents out on their first date.

In 2011, not long after my grandmother passed, I joined the Downtown Louisville Rotary Club. Her absence lingered in the quiet corners of my life — not sharp, but ever-present, like a door left slightly open. At her funeral, I carried her coffin. I couldn’t hold back the tears — not from the weight of grief alone, but from the memory of all the love she had shown me, year after year, in ways both quiet and profound.

That fall, I was selected for a one-month Group Study Exchange trip to Germany. We stayed in the homes of local Rotarians, living alongside them, sharing meals, trading stories. It was more than a professional exchange — it was a homecoming of sorts. A way to walk the same ground my ancestors had once known. To reconnect with roots that had been scattered by time, ocean, and war. A way, perhaps, to carry something of my grandmother with me — and offer it back to the land she had come from, generations before.

I didn’t know then that another branch of my tree would fall so soon. A year later, I would lose my father — her oldest son — without warning. Two generations, gone in quick succession. The loss hollowed something in me. But it also made the stories matter more.

It was early 2012, just after that trip, when I attended a small welcome dinner for new Rotary members at Vincenzo’s Restaurant. I was seated beside another new member — a man named Steven Schmidt. Both of us, in our own quiet ways, had been drawn to Rotary for something larger than ourselves: service, connection, continuity — the hope that our efforts might ripple outward, quietly shaping lives we’d never even meet.

We struck up a conversation — the kind of easy back-and-forth that happens when two people share a city, a history, a way of speaking.

At one point, he mentioned his grandmother.

“Her name was Anna,” he said. “Anna Margaret Thomas.”

Something stirred.

“Whelan?” I asked.

He smiled. “Yes. Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas. Did you know her?”

Aunt Mag.

I paused, then smiled. “Not in person,” I said. “But I knew her — through the stories my grandmother told. And you may not know this, but your grandmother set up my grandparents on a blind date in 1937. Had she not played matchmaker, I wouldn’t be sitting here — or telling you this story.”

Sometimes, I think life has a quiet way of introducing us to the people we’re meant to know — whether by grace, by timing, or by the gentle nudge of ancestors who aren’t quite finished connecting us.

Steven was quiet for a moment, visibly moved. He’d never heard the story before. “I had no idea,” he said. “That’s incredible.” He told me how meaningful it was to learn that his grandmother’s quiet instinct had helped shape another branch of the family tree — one he hadn’t known he was connected to.

Steven, I learned, was a business deal maker by profession — which felt fitting, considering the quiet matchmaking his grandmother had brokered decades earlier.

It was a full-circle moment. The story of the blind date, the dance, the flood, the canoe, and the family that followed — it had been told to me many times over the years by my grandmother. And in every telling, Aunt Mag’s name carried weight. She wasn’t just remembered. She was revered.

Now, her grandson was sitting beside me, in the same city, at the same table — 75 years after her quiet act of matchmaking changed the shape of a family.

The spark she lit in 1937 is still burning — not just in memory, but in the lives that followed.

Sometimes, the past doesn’t feel so far away.

Sometimes, the people who changed everything leave ripples that never stop reaching.

Floods come.

They rise, destroy, and remake.

They erase old paths — and carve new ones.

Louisville knows this all too well.

The city just weathered another historic flood in 2025 — the eighth worst in its recorded history.

And as the waters crept up again, so did the memory of 1937,

when a young man paddled a canoe through the city — not to flee, but to find someone.

Mary Lee and Wilbur met on dry ground,

but it was the rising water that revealed who they truly were.

Not swept away — but carried forward.

He came for her in a canoe.

She saw him — and knew.

From that moment on, the river was no longer something to fear.

It became the current that began a family —

guided first by love, and just a little by Aunt Mag.

Their love still follows the bends of the floodline.

And from that first rescue, seventy-six hearts have taken shape —

each beating its own rhythm,

yet marked by Wilbur’s quiet strength,

and the quiet beauty Mary Lee brought to everything she touched.

Even now, the story they set in motion carries us —

gently, steadily — toward higher ground.

Epilogue: One More Ripple

In the years after our conversation, Steven and I occasionally shared family stories over email — threads from two branches that had unknowingly grown from the same root.

Steven Louis Schmidt passed away on December 14, 2021, while I was out of the country. He was the grandson of Aunt Mag, the matchmaker who helped spark this story, and he had never known the full extent of her role until we sat beside each other that night.

A business broker by profession, Steven had a quiet gift for connection — something he may well have inherited from his grandmother.

I was grateful to tell him the story.

And even more grateful that, in some way, he became part of it — another ripple in a river that’s still carrying us forward.

Notes Behind the Story

The Great Flood of 1937

Louisville Metropolitan Sewer District, “Floodwall History and Facts,”

National Weather Service, “The Great Flood of 1937”

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Ohio River Flood History Archives

Courier-Journal archival reporting, January–February 1937

Mary Lee Zweydorf and Wilbur Anthony Padgett

Oral history interview with Mary Lee Zweydorf Padgett, March 1990

Padgett Family Archive: family photographs, wedding records, and written reminiscences

Marriage Record, St. Cecilia Catholic Church, Louisville, Kentucky, 1938

Obituary of Wilbur Anthony Padgett, Louisville Courier-Journal, 1986

Obituary of Mary Lee Zweydorf Padgett, Louisville Courier-Journal, 2011

Anna Margaret Whelan Thomas (“Aunt Mag”)

Marriage Record: Anna Margaret Whelan and James Kelly Thomas, Vine Grove, Kentucky, November 12, 1912

Family records shared by descendants, including Steven Schmidt (2012–2018)

Personal conversation between author and Steven Schmidt, Downtown Louisville Rotary Club Welcome Dinner at Vincenzo’s Restaurant, January 2012

Contextual Material

Jefferson County Floodplain History Map Layer (Louisville/Metro GIS Consortium)

Casa Madrid Ballroom: Louisville Dance Halls, University of Louisville Archives; Courier-Journal

U.S. Census Records, Portland Neighborhood Enumeration, 1920–1950

History of Armour-Klarer Company - Broecker Family website www.broeckerfamily.com

I really love all the photos you used. You can tell that they were happy.

What a wonder story and great tribute. I really enjoyed reading