The Dead Are Still Here

Before the boulevards and bourbon, there were burials.

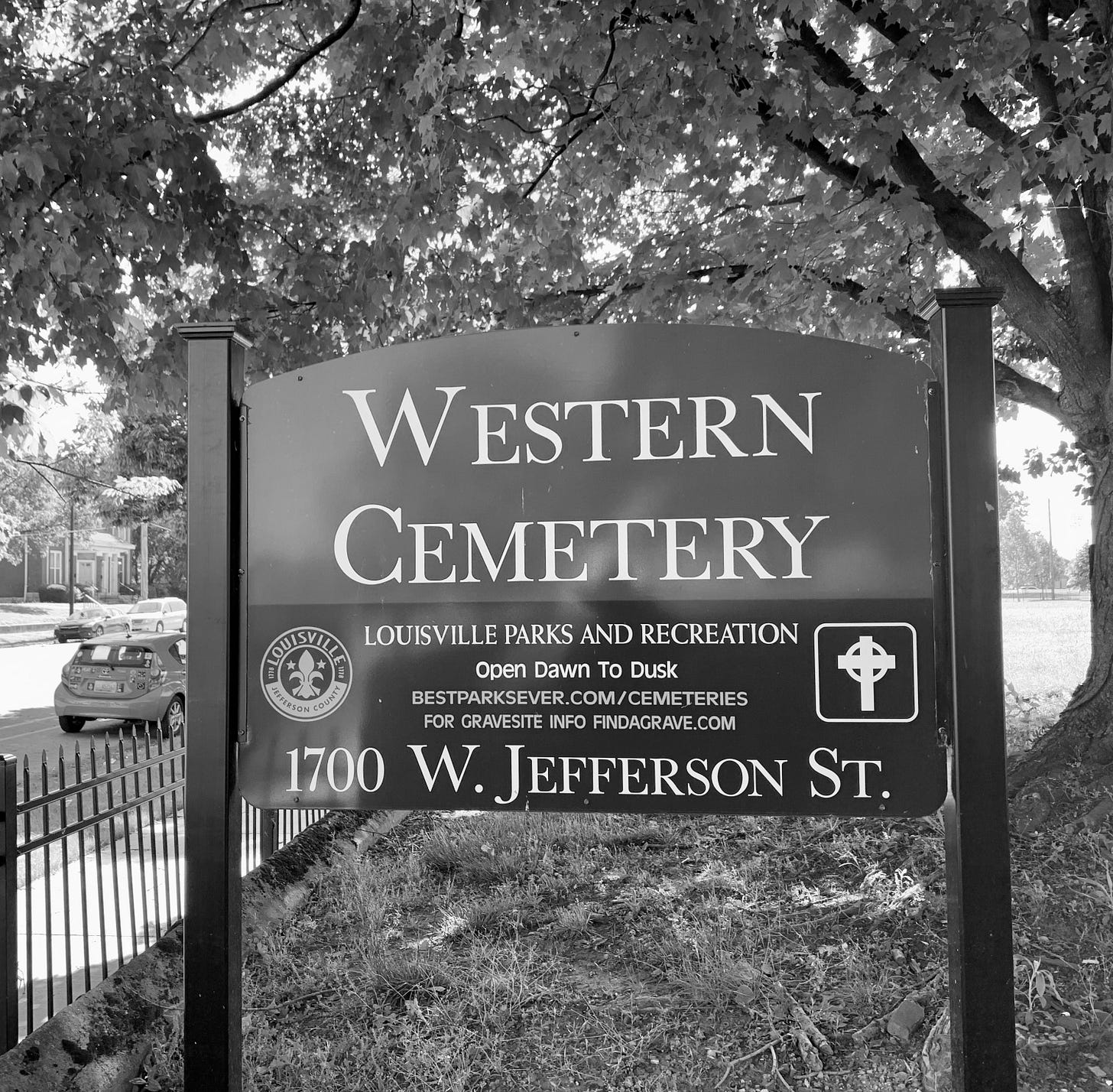

You could pass by without a second glance.

Most people do.

Western Cemetery doesn’t raise its voice.

A small city sign marks the spot, but it’s easy to miss—

just a patch of clipped grass behind a weathered fence on Jefferson Street.

Ordinary. Overlooked. Silent.

But this is no empty field.

From 1832 to 18931, nearly 5,000 souls were laid to rest here.

Louisville’s early dead.

Flatboat men and midwives,

enslaved children and free Black tradesmen,

immigrants, soldiers, the unnamed.

Layer upon layer.

Story upon story.

Buried without fanfare.

There is a monument, yes—but it speaks for few.

Most remain unmarked. Unknown.

But make no mistake—this is sacred ground.

A city’s beginnings lie here, just beneath the silence.

The morning was brilliant. The sun was high, the sky rinsed clean after a violent windstorm had swept through Louisville the night before. Trees had fallen. Tens of thousands were without power. But here, in the stillness of this forgotten ground, there was light—sharp, revealing light. As if the past had been waiting for just the right angle of sun to be seen again.

Western Cemetery was established in 1830, Louisville’s second public graveyard, back when the river still governed the rhythm of life and death. Today, most of its markers are gone. Stones lie broken or swallowed by earth. Entire rows have vanished. The dead remain, but the names have thinned.

On May 17, 2025, I joined a walking tour led by Kaira Tucker2, supervisor of the Kentucky History Room at the Louisville Free Public Library. She mentioned she’s not a Louisville native, but you’d never know it. She greeted us with a warm smile, handed out copies of old maps, and spoke with quiet reverence, naming what the city had tried to forget.

At the edge of the cemetery stands a low stone monument, etched with a map:

Roman Catholics.

Strangers.

Private Lots.

Louisville Public.

Africans.

These weren’t just divisions of space—they were divisions of belonging. In death, as in life, the city remained segregated: by faith, by fortune, by color, by status.

The Catholic section once held parishioners from Portland and the West End3, buried with sacrament and familiarity4. The Private lots were purchased, landscaped, visited. The Louisville Public section was for the city’s poor—those buried at public expense, many without stones. And in one corner was the section once labeled Africans—the final resting place for both enslaved and free Black residents, buried before and after the Civil War.

But it was the Strangers who gave me pause.

That word—Strangers—carved so plainly into the map.

This section was set aside for the unknown. In a river city like Louisville, people were always arriving—by flatboat, by packet, by sheer force of will—chasing work, fleeing memory, or hoping to begin again. Some never made it past the first night. They were found in boarding houses and alleyways, in saloons and in the river. Strangers with no one to claim them. No one to send word home.

They were buried here—lost to the city almost as quickly as they had entered it. Their names, if ever spoken, slipped away before they could be written down. And yet, for a moment, they were part of this place. A breath. A heartbeat. A chapter the city forgot to keep.

The Falls of the Ohio made this inevitable. The rapids turned the river into a trap, catching what the current couldn’t carry on—bodies snagged on driftwood, wedged between rocks, or washed ashore near the wharf. This wasn’t rare. It wasn’t even surprising. Local newspapers reported these discoveries with chilling regularity—“another unknown man pulled from the river,” they’d write, as if death by water had become part of the city’s rhythm.5

Some had fallen. Some had jumped. Some had been pushed. All were buried here. Their stories ended before they could begin. And their names—if they were ever known—slipped into silence, carried off like mist, before the morning ever noticed.

And yet—the stillness here speaks.

This isn’t unique to Louisville. In river towns across America, you’ll find these quiet corners. Sometimes labeled Strangers. Sometimes Unknowns. Sometimes left off the map entirely. In places shaped by flow—of people, freight, epidemics, disaster—these cemeteries absorbed those who passed through but never returned. A traveler. A refugee. A mother who died in childbirth far from home. A boy who drowned. A man with no papers. The river welcomed and took alike.

And maybe—just maybe—one of them was yours.

Most families have someone who disappeared. A name that drifts like smoke between the lines. A daughter who fades from the page. A brother swallowed by the silence of war. A great-grandmother glimpsed only in shadows. We call them “lost.” But perhaps they are only sleeping beneath the surface of time—unnamed, unremembered, but not unreachable.

Perhaps you’re searching for someone who was always missing—

and you’re the one who came back to look.

At Western, even the dead were not safe.

In the 1800s, a scandal surfaced: coffins were discovered empty. The cemetery’s sexton had been selling bodies to a local medical school—eight dollars apiece. The graves most often disturbed belonged to the poor, the unknown, the unvisited. Those buried in the Louisville Public and Strangers sections. Their names didn’t matter. Their bodies were seen as expendable. Even in death, they were exploited.

And then came the silence.

No outrage that lasted. No restitution. Just quiet. The kind that settles in the ground and stays there.

That knowledge changes how the air feels. You walk slower. You listen more closely. And you begin to understand: what lingers here isn’t just loss—it’s harm, left unacknowledged.

And yet, even in that silence, a voice can still be heard.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

—John Keats, Ode on a Grecian Urn

We stood near the Strangers section as Kaira read the lines aloud.6 George Keats, the poet’s younger brother, was once buried here—at Western. But like some others, his remains were later moved7. His name is still spoken here. The ground beneath him changed.

Not far from where we stood, the Jefferson Branch Library rises from a mound in the cemetery’s northwest corner. A Carnegie library, it closed in the 1970s due to budget cuts.

But the library itself was built atop graves.

Its foundation rests on the section once designated “Africans.”

No exhumations. No monument. No reckoning.

Someone thought this was progress—

to build a public library on land where ancestors lay buried,

unacknowledged and unmourned.

Just books above. Bones below.

And silence, holding it all together.

What does it mean to read stories

in a place built over the desecrated graves

of those the library claimed to serve?

Who looked at a cemetery and saw potential?

Who decided sacred ground could be overwritten by masonry,

so long as it wore the mask of civic good?

What kind of minds call that progress?

And what does it mean now—

to know all this now?

The silence is no longer innocent.

Burial for some in this city isn’t linear. It’s geological.

While some are laid to rest and left in peace, others are layered over—

compacted, erased, and then, sometimes, they rise back up.

No known master register survives for Western Cemetery. The sexton’s records, for now, are lost to time. But two sisters—Joan and Doris Batliner—spent years reconstructing what they could into a large database.

Doris was a chief librarian at The Courier-Journal, a USO performer in the 1940s, a Knight of St. Patrick by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and a local author8. Joan, a Catholic with a fondness for animals and Reese’s Cups, had a heart tuned to history9. Together, they pored over funeral home ledgers for Western, Portland, and St. John’s cemeteries, recording names, dates, fragments.

After Joan passed away in 2023, her estate donated their research to the Louisville Free Public Library10. It doesn’t hold all the names. But it holds some. And that is no small thing.

Just imagine what stories might be saved—what history might not be lost—if more people gave a little of their time the way these two sisters did: quietly, patiently, with no reward but remembrance.

Because cemeteries don’t preserve memory. People do.

In Louisville, our cemeteries carry more than bodies.

They carry damp wood and rosary beads.

What was buried, and what was believed.

Western feels both wild and watchful: a few scattered pink dogwoods, some shifting stones, distant traffic, and groundhogs slipping beneath the last surviving markers.

German, Irish, Black, and Appalachian.

The ones who built it.

The ones no one recorded.

And the ones still waiting to be found.

Each cemetery speaks in its own voice.

Some chant in marble.

Others murmur through weeds.

Western doesn’t shout. It listens.

It keeps what the city forgets—and gives it back slowly,

when the light is just right, and the wind is kind.

These places are not ruins.

They are thresholds.

Not endings, but openings.

The groundhogs had vanished by the time I left.

But their holes remained—scattered like questions in the grass,

reminders that the ground is never as still as we think.

Western is still giving up its stories. One small opening at a time.

And if you stand there long enough—if you let the light shift, and the clover sway, and your imagination reach deeper than the map—

you might feel someone looking back.

Not haunting.

Just hoping.

That someone, someday, might remember they were here.

Might speak their name.

Might finish their story.

Copyright 2025 Christopher Padgett

“Old Cemeteries of Louisville.” Jeffersontown Historical Museum Web Archive.

Public Tour conducted by Kaira Tucker, Supervisor, Kentucky History Room, Louisville Free Public Library, 17 May 2025

Filson Historical Society Western Cemetery Files

“Western Cemetery.” Find A Grave.

Historical accounts indicate that 19th-century Louisville newspapers frequently reported instances of unidentified bodies recovered from the Ohio River, reflecting the river's perilous nature and its role in the city's history.

“Ode on a Grecian Urn,” John Keats, 1819

“George Keats” entry, Cave Hill Cemetery interment records, Louisville, Kentucky

Obituary of Doris J. Batliner, 27 March 2009

Obituary of Joan M. Batliner, 28 November 2023

Louisville Free Public Library, Kentucky History Room (including records donated by the Estate of Joan Batliner, 2023)

What a love letter to a cemetery. Beautifully done!

I so enjoyed reading this. You have a quite a gift for storytelling. Beautifully written.