The Ink Between Us

Two Crossings, One Century Apart

In the early 20th century, young couples from Louisville would slip across the Ohio River into Clark County, Indiana, to be married. The reasons were practical—yet tinged with romance. Indiana’s marriage laws were far more forgiving than Kentucky’s. No waiting period. No witnesses. And an eighteen-year-old woman could marry without a parent’s consent.

The newspapers of the time even carried discreet advertisements: “Marriages performed promptly at any hour. License issued while you wait.” Jeffersonville justices kept their lamps burning late, and the ferry operators could spot exactly which passengers were bound for the clerk’s office.

People began calling Clark County “Louisville’s Gretna Green,” borrowing the name from the famous Scottish border village where, since the 18th century, English couples had fled to marry under Scotland’s more lenient laws.1 Just as Gretna Green lay only a quick ride over the border from England, Jeffersonville and Clarksville lay just a brief ferry trip over the Ohio from Louisville. Cross a line on the map—and the rules changed.

My great-grandparents, Tom and Clara, made that crossing in 1914. She was seventeen, he was twenty-one. They boarded a paddlewheel packet boat, its great wheel pushing the muddy water behind them as the scent of coal smoke clung to their clothes. Deckhands coiled wet ropes on the deck, the whistle’s echo rolled across the river, and the Indiana shore drew near.

When they stepped off in Jeffersonville, they didn’t head for the courthouse but for a small clapboard building near the railroad tracks, its sign impossible to miss: Marriage Parlor — License Procured Here.2 The magistrate’s shingle hung just above the door, and inside, Magistrate Oscar Hayes3 waited at his desk.

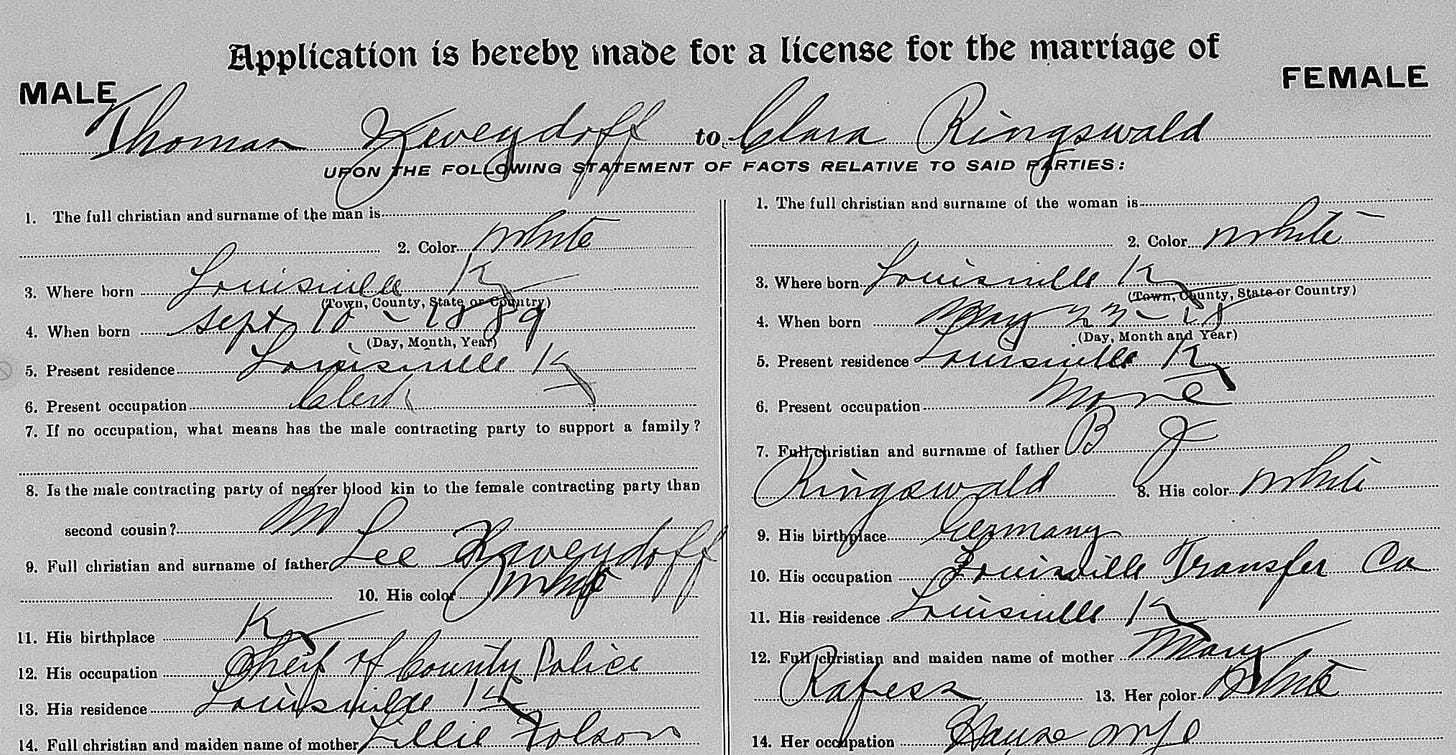

On the application, her penmanship is confident and steady—until she reaches her birthdate. Clara had moved through the top of the form with assurance—her name, his name, the town she now called home—each letter sure and untroubled. But when she reached the year of her birth, the pen hesitated. She wrote “18” in a clean, deliberate hand…and then stopped. The line breaks off into nothing, a stark white space where the final two digits should be.

This was no ordinary date. Years earlier, after her mother died young, Clara had been placed in the House of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic orphanage on Bank Street.4 Tom grew up in a home just across the street, close enough to see the orphanage yard, close enough for his life to be stitched to hers before either of them understood the pattern. For Clara, this paper was more than a license—it was a key. On the other side of it was the boy she had once seen from the other side of a fence, now the man she meant to tether her life to.

It’s the absence that shouts. She could not bring herself to write the truth, and she would not tell a lie. So she left it hanging—half a year, half a fact—hoping that blank space might be enough to carry her across.

The first time I examined this record, nearly a hundred years later, I leaned closer, drawn into that tiny square of paper as if it were a doorway. My own pen was in my hand—taking notes—when I realized hers had been there too, in this same suspended moment, wrestling with what could be said and what must be hidden. In that instant, I wasn’t just looking at an old marriage application. I was watching Clara make a choice. And she chose to keep writing.

And yet, as I studied it longer, the blankness between those numbers began to feel less like omission and more like a whisper—one meant for me. She could never have imagined someone tracing that line a century later, hearing her voice in the space she left behind. But I did.

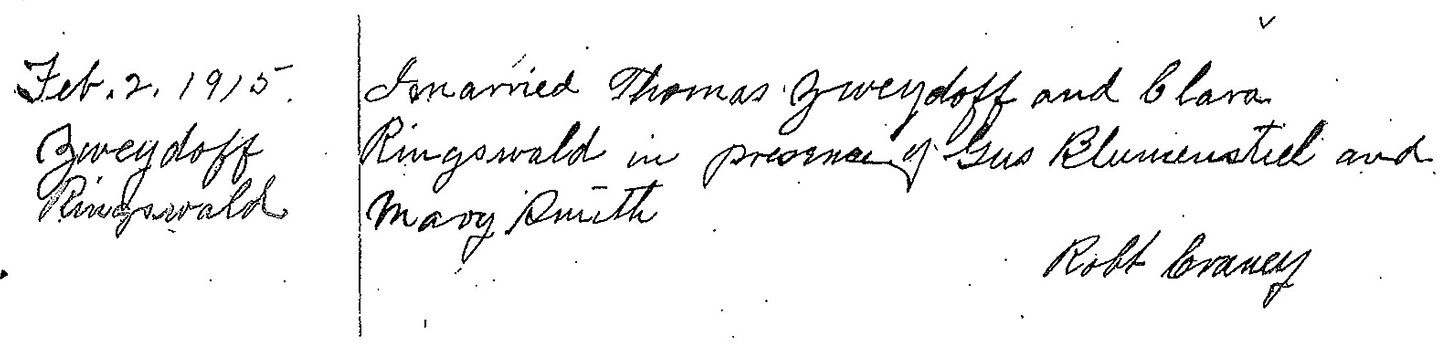

A year later, Tom and Clara married again—this time in their neighborhood church, Saint Cecilia’s,5 in Portland, Kentucky, just across the river. Proper witnesses, proper blessings, everything above board. In the eyes of the Church, perhaps this was the “real” wedding. But in Clara’s heart, I suspect the real wedding was the one where she took the risk and left the truth half-written.

They were both descendants of German immigrants. So were we.

More than a century after that first crossing, I made my own—not by ferry, but in a German-made car, its tires humming over the Abraham Lincoln Bridge.6 We signed the papers, then drove home the other way, across the John F. Kennedy Bridge, sunlight glinting off the water below. It cost $69, a few signatures, and an officiant from the clerk’s office.

When the paperwork was done, the women behind the counter clapped. “How long y’all been together?” one asked. “Twenty-three years,” I said. Audible gasps. The clerk who helped us smiled and said, “I wasn’t even born then.”

And when I bent to sign my name, I thought of Clara—seventeen years old, crossing this same river with her heart pounding, holding her breath as she wrote a date she couldn’t bring herself to finish. My pen moved steadily, but hers stopped short. A hundred years apart, the ink linked us.

They stayed married for thirty-two years, until cancer took her. The marriage produced ten children, forty-nine grandchildren, and one hundred and three great-grandchildren—of which I am one. My great-grandfather was born in 1889, the same year the Eiffel Tower first rose above Paris, yet he lived long enough for me to know him, to remember the warmth of being near him. I was a boy, but I can still call up the sound of his voice, the feeling of his presence. He belonged to a century I could only imagine, but he lived to touch my own.

The Ohio River has always been more than a line on a map. It is a border, yes—but also a bridge. For generations, it has carried people toward what they couldn’t find at home: freedom, safety, love, or just a little less red tape. Clara crossed it at seventeen, heart pounding, with a secret in her handwriting. I crossed it more than a hundred years later, fully aware of her story, her courage echoing in my own.

The river has a memory. It remembers the enslaved men and women who rowed across under cover of night, risking everything for freedom. It remembers runaways and rebels. It remembers the lovers who came with their secrets and left as newlyweds. It has held in its current the sound of hurried footsteps on ferry decks, the scratch of pens on courthouse ledgers, the sighs of people stepping back onto shore with their lives newly bound to someone else.

The river doesn’t care who you are. But it notices. Like ink, it keeps the imprint of every crossing—of Clara’s hand that hesitated, and of mine, steady a century later, turning the page to find hers still there.

Some places don’t just hold history—they give it back to you. The Ohio River is one of them.

Copyright 2025 Christopher Padgett

The term Gretna Green originates from a Scottish village just over the border from England. Beginning in 1754, English marriage laws required parental consent for those under 21, prompting young couples to elope to Scotland, where the laws were more lenient. The name became shorthand for any border town where marriage was quicker and easier than at home.

Marriage parlors in Jeffersonville were often operated by magistrates or justices of the peace and were concentrated near the ferry landings. They served both locals and out-of-towners, advertising in newspapers and keeping irregular hours to accommodate late-night arrivals.

Magistrate Oscar Hayes is documented in Clark County records as officiating hundreds of marriages during the 1910s and 1920s.

The House of the Good Shepherd was a Catholic institution for girls and young women, including orphans, located on Bank Street in Louisville, Kentucky.

Saint Cecilia Catholic Church, established in 1873 in the Portland neighborhood of Louisville, Kentucky, served generations of immigrant families and remains a local landmark.

The Abraham Lincoln Bridge (northbound) and John F. Kennedy Bridge (southbound) now carry Interstate 65 traffic across the Ohio River between Louisville and Jeffersonville.

Wonderful story. I love that the Ohio River was an important piece in your and your ancestor's lives. Living all of my life near the Ohio I have fond memories of that line between two states. Reminds me that I need to tell my story about it. Again, great story.

This is so beautifully written @Christopher Padgett. It captured me from the start. I felt like I was on a journey with anyone who had ever crossed the river with a secret ... And the photos made it extra special!