Why Is Louisville Hiding Its Namesake?

What disappears, what remains—and how one hidden statue reveals the city’s uneasy relationship with its own past

Louisville bears his name. But his statue—his likeness, his presence—has been hidden from view.

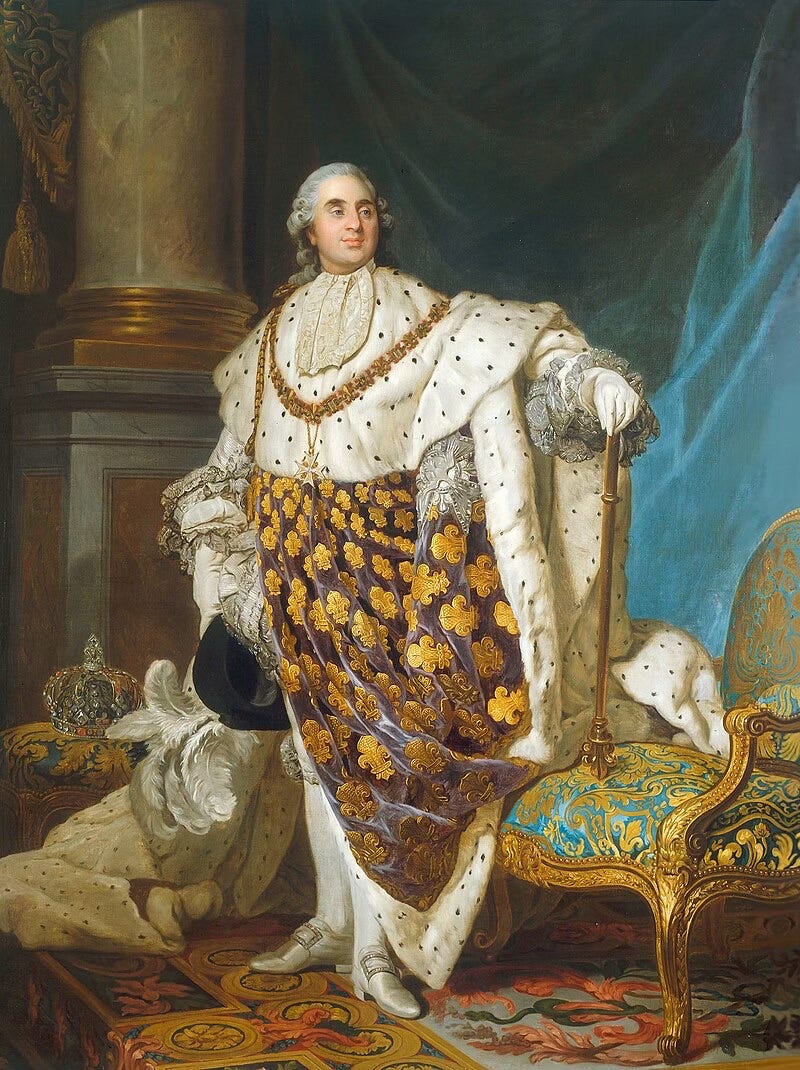

Somewhere in a locked city storage facility lies a nine ton Carrara marble statue1, weathered and silent. It’s the likeness of King Louis XVI, a gift2 from Louisville’s sister city Montpellier, France—a symbol of old-world allegiance to a young American cause. It was originally commissioned by his daughter, Marie-Thérèse, in honor of her father’s legacy. For years, he stood downtown with an outstretched arm, reminding us of a time when revolutionaries needed friends.

That reminder feels more urgent now than ever. We’re living in a time when long-standing alliances are dismissed as outdated, when loyalty between nations is treated as optional, and when history is edited to fit the politics of the moment. But memory—real memory—pushes back. It insists that we not forget who stood beside us, and that we don’t erase the debt simply because it’s inconvenient to honor.

Today, the statue of King Louis XVI sits in exile. Not because of his crimes—he was no tyrant—but because history got swept into a moment of pain, and we didn’t yet know what to do with the past.

This isn’t just any statue. It’s the only public monument to King Louis XVI in the United States3. A singular tribute to a monarch who, despite his flaws, backed a republic in its infancy. Its quiet exile today reveals less about the man himself than about our modern struggle to face a past that refuses to be simple.

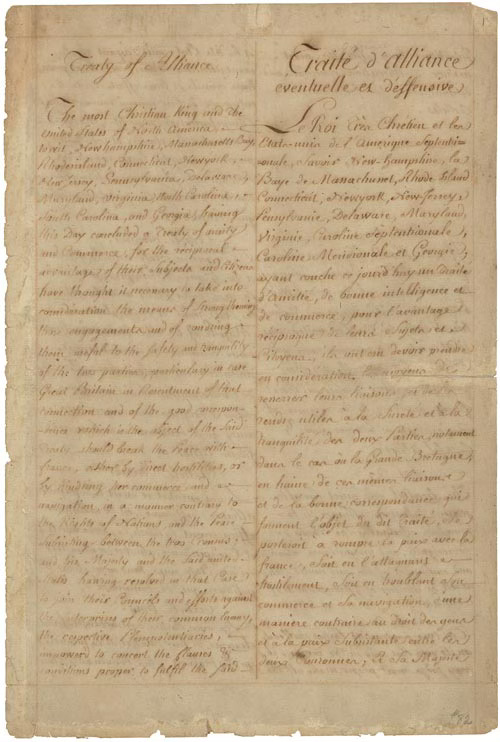

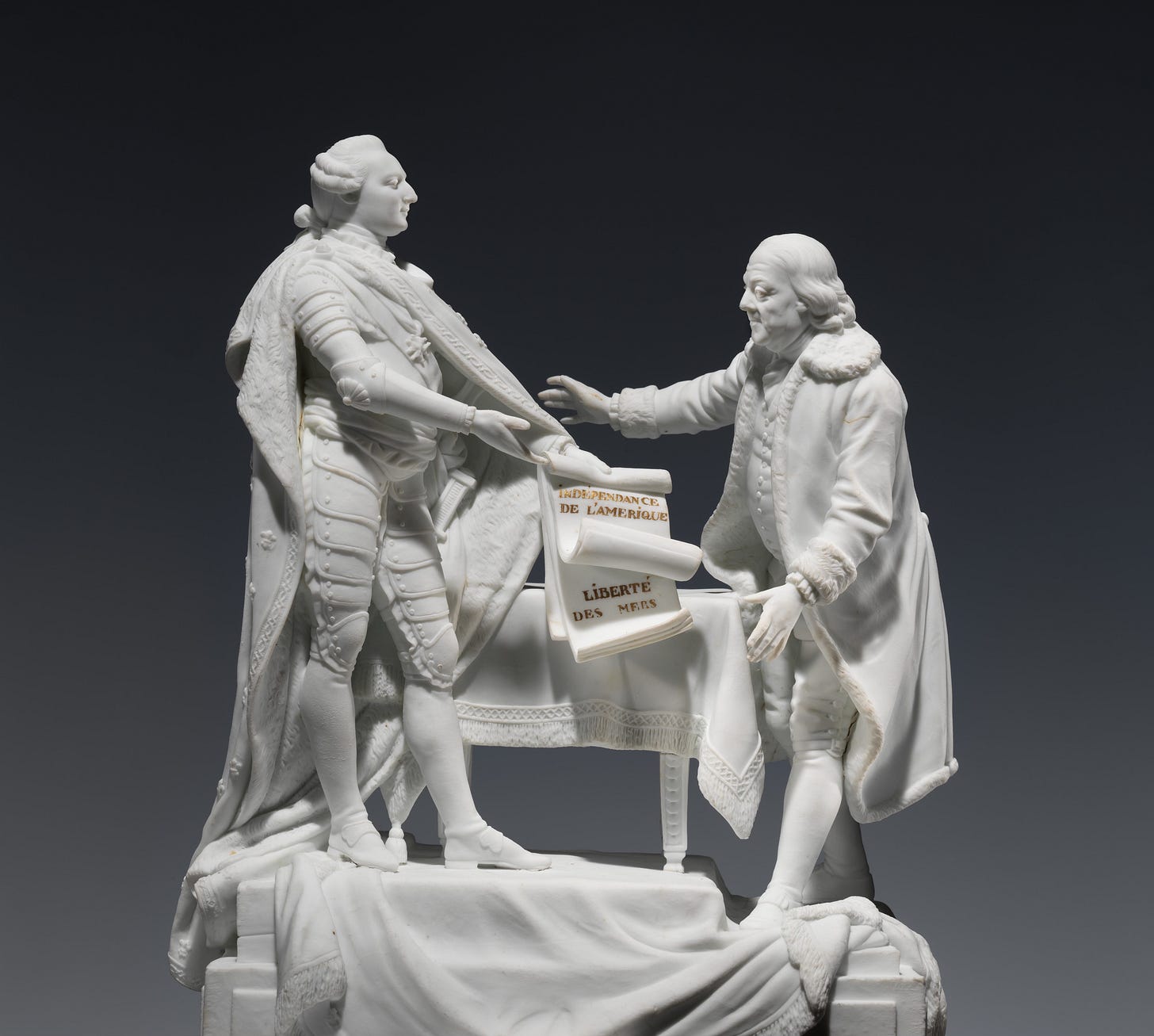

In 1778, France cemented its alliance with the American colonies through two landmark treaties—one of friendship and commerce, the other a military pact pledging mutual defense. These agreements gave the revolution legitimacy on the world stage. France recognized American independence, promised naval and military support, and committed itself to a war against Britain on our behalf. King Louis XVI made that call. They sent ships, soldiers, muskets, and ideals. At Yorktown, French cannons and troops fought alongside Americans. Without them, we might have lost. Without him, we might never have won.

France, under his rule, gave more than 1.3 billion livres4—an amount estimated to exceed $13 billion today—to support the American Revolution.

On May 1, 1780, the Virginia General Assembly officially chartered the town and named it Louisville in honor of King Louis XVI, recognizing his support of the American colonies during the Revolutionary War.5

Louis placed a bet on a fragile republic, and this river city was given a royal name to honor him.

Now removed from the public square, his statue sits in silence—set aside, as if putting it away might quiet the questions it raises.

At some point during the protests of 2020, the statue’s outstretched hand—once extended in welcome—was torn off. It was never just a hand. It was a gesture: of alliance, of recognition, of shared cause across an ocean and across time. That it now lies broken feels less like vandalism and more like a metaphor we haven’t fully reckoned with. An open hand—once symbolizing the bond between Louisville and the ideals that shaped America—reduced to a jagged absence. It invites a harder question: what does it mean when the very symbols of unity and shared purpose are the first to fall? And what do we lose when we stop recognizing the hands that once reached out to help us rise?

Louisville is home to the national headquarters of the Sons of the American Revolution—a city shaped by revolution, named in gratitude, and entrusted with memory6. That makes the silence around the statue not just local, but national. It asks whether we still know how to hold complex legacies, or if we’ve grown too quick to drop them.

We’re right to question monuments. Statues help us understand—or weigh us down. King Louis XVI was neither a Confederate general nor an architect of empire. He was a monarch, yes, and he presided over a colonial system—but he also funded liberty abroad, not conquest. He abolished judicial torture and encouraged smallpox inoculation after the death of his grandfather, Louis XV. He also granted civil rights to non-Catholics through the Edict of Versailles7—an important gesture of religious tolerance in a deeply divided France. He tried to reform an unyielding system, but not fast enough—and not deeply enough—to stop the tidal wave of revolt. In the end, his hesitation and privilege made him both a reluctant reformer and a symbol of the old order’s failure. It cost him his crown and his life.

He died not with rage, but with resolve. At the scaffold in 1793, he forgave his executioners and prayed for the nation that no longer wanted him. Whatever else he was, Louis was not indifferent to suffering. That, too, is part of the story.

The vandalism of his statue in 2020 came during a tidal wave of reckoning—a justifiable outcry against injustice. But justice, if it’s to be more than reaction, must be tempered with discernment. We cannot afford to cast away history wholesale. To do so is to abandon the nuance we desperately need.

This statue, this carved figure, isn’t just about a king. It’s about a city that has always lived in the in-between—Southern and Northern, river and rail, bourbon and backbone. A melting pot of industry and influence, where immigrants, revolutionaries, refugees, and formerly enslaved people8 came to build new lives. A city built on crossroads and contradictions, where history doesn’t sit neatly in one column or the other. Louisville has always been a place of blurred lines and layered identities, a place where past and present overlap. The story of King Louis XVI fits here not because it’s easy, but because it’s complex. It asks us to hold more than one truth at once.

In 2025, Louisville marks the bicentennial of the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit—a celebration of friendship, freedom, and shared ideals. Lafayette’s name still rings with glory: the hero of two revolutions, the face of principled resistance, the Frenchman Americans love to remember.

But Lafayette’s triumphs were built on foundations laid by Louis XVI. Before Lafayette ever set sail for America, it was the king who risked reputation and treasure—sending ships, soldiers, and funds when our cause was still fragile. Louis never walked these streets, but his decision made Lafayette’s mission possible: in every cannon at Yorktown, every French transport braving the Atlantic, every alliance forged in hope.

Their legacies aren’t separate stories; they’re chapters of the same narrative. One provided the means, the other carried the promise forward. As we raise our voices for Lafayette, let us also honor the monarch whose gamble helped win our freedom.

We have a choice. Leave King Louis hidden, his broken hand a gesture we no longer recognize. Or bring him back, interpreted with thoughtfulness and clarity. Let him stand not as a symbol of domination, but of unlikely friendship that helped shape who we are.

Somewhere along the way, even his name started to fade. Louisville—the city named in his honor—has been repackaged so many times it now wears its pronunciation like a joke. In the early 2000s, a tourism campaign leaned into the gimmick, listing every possible way people mispronounce the name: Lou-ee-ville, Loo-a-vul, Luhvul, Loo-vil. It was pitched as clever. It took a name rooted in revolution, alliance, and sacrifice, and turned it into a joke.

Even our flag, once considered one of the best in the nation9, was stripped of its dignity. The original 1949 city flag featured 13 stars for the colonies and three fleur-de-lis for the French crown—a striking, award-winning design that tied Louisville to its revolutionary roots.

But after the city-county merger in 2003, we replaced it with something far less inspired: a corporate-looking seal with clip-art sensibilities, circling a fleur-de-lis like it’s trapped in a brand manual. It kept the symbol but lost the story.

Not all civic branding gets it wrong. In 1982, the city commissioned a theme song10 titled “Look What We Can Do, Louisville.” It was performed by Hazel Miller, a powerhouse Louisville-born singer whose voice carried not just the lyrics, but the soul of the city itself.

Written by Nancy Moser and Joe Brown, the song has all the hallmarks of its era—synth lines, soft horns, a touch of cornball charm—but it also had something far rarer: authenticity. It didn’t reduce the city to quirks or gimmicks. It didn’t try to be clever. It tried to be proud. “Look what we can do, Louisville,” the chorus rang out, not as a boast but as a promise. There was grounded optimism in it—a belief that the city’s best days weren’t behind it, but still ahead.

Hazel Miller would go on to perform the song again decades later, including at the 2023 mayoral inauguration—a reminder that some symbols stick because they speak to something true.

So it's not just the statue that’s been hidden. It’s the meaning.

Names matter. Symbols matter. They tell us where we come from—and what we’ve chosen to honor. Hiding the statue is one form of forgetting. Flattening the city’s name into novelty is another. Replacing a powerful flag with one that could hang in a bank lobby is yet another. All of it reflects a discomfort with complexity, a desire to sell the city without having to understand it.

And in doing so, we lose sight of what made that name matter in the first place: a king who bet on our freedom when the outcome was still uncertain. A French alliance that helped make the United States possible. That kind of loyalty—personal, political, and profound—deserves more than storage and slogans.

Restoring the statue isn’t about glorifying monarchy. It’s about honoring the moment he chose our freedom over neutrality, at a time when the outcome was still uncertain.

More than that, it means choosing understanding over erasure.

Louisville is a city with a long memory. Our ancestors settled its edges, raised children in shotgun houses, made hard choices on muddy streets and in candlelit rooms, not far from the Ohio’s banks, where flatboats carried families and freight toward the frontier.

Some fled one revolution. Others lit the match for another. They built lives from borrowed hope and stubborn will.

Our history is not a burden—it’s a landscape to explore.

Let’s bring Louis back into the light—not to glorify the past, but to keep the story alive. The hand is broken now, but the gesture remains—a reminder that memory isn’t meant to be buried. It’s meant to be met.

Copyright 2025 Christopher Padgett

If this spoke to you, hit the heart icon so it can find its way to more curious minds. And if you haven’t subscribed yet, now’s a good time to join the conversation. I’ve got many more stories to tell.

Statue details: The statue, carved in Carrara marble by Achille-Joseph Valois between 1825–1829, weighs approximately nine tons.

Source: Louisville Metro Government archives; public records from the Office of Arts & Culture.

Sister city gift: Montpellier, France, Louisville’s sister city, gifted the statue in 1967 as a symbol of friendship.

Source: City of Louisville press release, 1967; Louisville Metro Government.

Only U.S. Statue of Louis XVI: The statue of King Louis XVI in Louisville is the only known public monument dedicated to the French monarch in the United States. It was gifted by Montpellier, France, in 1967. Source: Louisville Metro Government; Achille-Joseph Valois, sculptor (1825–1829).

Revolutionary aid estimate: France’s support totaled more than 1.3 billion livres. Modern economic estimates convert this to roughly $13–15 billion.

Source: John Hardman, Louis XVI: The Silent King, 2000.

Founding of Louisville: The Virginia General Assembly officially chartered Louisville on May 1, 1780, naming it in honor of King Louis XVI of France in recognition of his alliance with the American colonies.

Source: Commonwealth of Virginia legislative records; Encyclopedia of Louisville.

Louisville as SAR Headquarters: The national headquarters of the Sons of the American Revolution is located in downtown Louisville, reflecting the city’s long-standing ties to Revolutionary history. Source: sar.org.

Edict of Versailles (1787): Also known as the Edict of Tolerance, this decree granted civil rights to French Protestants and other religious minorities, ending nearly a century of legal discrimination. Source: Wikipedia, “Edict of Versailles.”

Post–Civil War Migration to Louisville: After emancipation, Louisville became a central destination for formerly enslaved people from across Kentucky and the South. Black communities grew rapidly in neighborhoods such as Smoketown, California, and Russell. Source: Kleber, John E., ed. The Encyclopedia of Louisville. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

Original Louisville City Flag: Designed in 1949, Louisville’s original flag featured 13 stars and three fleur-de-lis. In a 2004 North American Vexillological Association (NAVA) survey, it ranked as the 9th best city flag in North America. Source: NAVA Survey 2004.

“Look What We Can Do, Louisville” (1982): This city pride anthem was written by Nancy Moser and Joe Brown and performed by Louisville-born singer Hazel Miller.

We were in Vienna recently and our tour guide (entertaining but not the most historically accurate) brought us to a desecrated statue of Dr. Karl Luger. When I asked what happened, he told me - paraphrasing here - that when American blew up in 2020, some fringe groups in Vienna decided to follow suit, and destroyed or removed a number of monuments amid chants of BLM.

He said it broke the city’s heart, and now no one has the courage to clean it up. 💔

The truth is a bit more nuanced - complex ideas of history always are when emotions and performative outrage take over the spots reserved for critical thinking and fact.

I’m with you, Christopher, Louisville’s namesake should be protected and seen, not hidden away or, forbid, destroyed.

First time reader and commenter. Love this thoughtful piece. The events of 2020 had so much of an impact on us and I appreciate hearing what happened where you were. Where I am Lancaster County, PA they tried to burn down the courthouse for a week. People were arrested and jailed, but they then went after the judge and his family. We cant forget what happened.